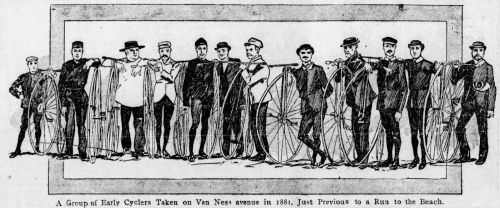

FIRST BIKE ON THE COAST. - The San Francisco Examiner, 04 Aug 1895

THE FIRST BIKE ON THE COAST.

It Belonged to Colonel Ralph de Clairmont, and Came Here in 1876.

Hardships Endured in San Francisco by the Pioneer Riders of the Gigantic Wheel.

STEALING SPINS IN THE PARK.

First Wheelmen on the Coast - Military Resections on the Government Reservation - Meets, Runs and Feeds.

When you meet a very old gentleman, with snowy hair and beard, spinning on his wheel through Golden Gate Park in the early morning hours, do not refer to him as that old fellow, and refrain from any flippant or trifling remarks about the whiteness of his hair, his probable age, his pose in the saddle, nor the gay-colored ribbons which adorn the handle bar of his machine. That old gentleman, sitting erect in his saddle, like a cavalry officer and guides his wheel over the driveways and paths with such remarkable precision is Colonel Ralph de Clairmont, the father of cycling on the Pacific, and one of the very first wheelmen on the American continent. He rode the wheel when most crackerjacks of to-day were rocked in the cradle, and many other riders had not even yet seen the light of day. He knows the origin and history of cycling from the very beginning and can tell when and where the first wheel was made, and has followed the various degrees of improvement on the machine from the first to the present.

The bicycle is a French invention. The first wheel was made in France about twenty years ago; a single high wheel, with a small one in the rear. Soon thereafter some bicycles were made in Coventry, England, and later they were improved upon in the United States.

Little do our cyclers know of the troubles and difficulties which beset the pioneer wheelmen in their struggles to pave the path for the riders of the present and future generations. Their recital makes a most interesting chapter.

Colonel de Clairmont imported his first machine, the high wheel pattern, from Paris to this city in the spring of 1876. His was the only bicycle on the Coast, from the Bering straits to the straits of Magellan, and the third or fourth wheel on the western hemisphere. His maiden spin to the Cliff House caused a small stampede of horses in the Park and on the ocean beach, but no accident. During the following year G. Loring Cunningham received an English wheel from Boston, and shortly afterwards Governor Perkins, R. B. Woodward and J. B. Golly imported their wheels from Coventry, England. The wheels were high and difficult to mount. Mr. Woodward's machine had a sixty-inch front wheel, and it required two steps on the backbone to reach the saddle. Its gigantic dimensions and ungainly appearance caused considerable comment, not all of which was complimentary to the rider or machine, particularly the comment indulged in by drivers whose horses the machine scared.

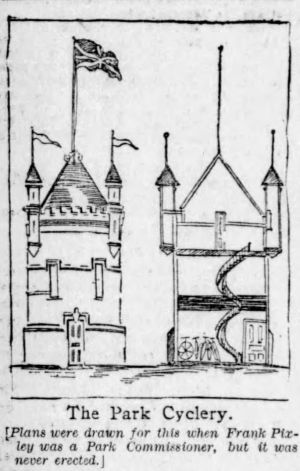

[Plans were drawn for this when Frank Pixley was a Park Commissioner, but it was never erected.]

The riders endured the stare of pedestrians and braved audibly derisive remarks from horsemen. They rode the high phantom wheel, spite of all danger, until more stout hearts augmented their numbers. These pioneer wheelmen organized the San Francisco Bicycle Club on December 13, 1878, at Union Hall. It was the first club in this city and second only to the Boston Bicycle Club, which had been organized a few months earlier. Colonel Ralph de Clairmont, Senator Perkins, H. B. Land, W. M. Fuller, G. Loring Cunningham, George H. Strong, F. G. Blinn, J. B. Golly and Charles L. Barrett were the charter members. Some of them still ride the wheel, but not the old style they had to climb in those days. Colonel de Clairmont was President of the club till 1881, when he was succeeded by Columbus Waterhouse. The club maintained its organization until two years ago.

[Only the holder of these coveted pieces of pasteboard could ride in Golden Gate Park, and then only on certain by-paths, and before 7 a. m.]

But the difficulties these pioneer wheelmen encountered seemed almost insurmountable. The machines were large and unwieldy, the mounting required the agility of an acrobat, the riding was fraught with danger. A fall from such altitude easily resulted in severe injury. A rut in the road, a stone or fragment in fact, the least impediment would hurl the luckless rider from his perch some distance ahead of his tall steed, and the fall was usually attended with much more danger and often pain than a fall from a modern safety.

The roads in those days were in a most execrable condition. The very best pavement in San Francisco was of cobbles, except a small patch of concrete in front of the Palace Hotel, which was eagerly hugged by every rider who had nerve enough to brave the stares of a gaping crowd, for a bicycle in those days attracted as much attention as a circus.

To make a mile in three minutes was considered excellent time, and when Herman C. Eggers, now of Fresno, accomplished his run of 500 miles in three days at the old Mechanics' Pavilion he was regarded the hero of the day. But the Pavilion was not available at all times, the streets entirely unfit for the wheelman's use and the Park was not to be desecrated by the silent steed. The protests from owners of carriages were too powerful. The Park Commissioners and their wealthy and influential friends owned carriages, and they would not think of allowing the frightful machines to run amuck in the driveway, sacred to carriages and horses only. They pictured the horrible accidents which were unavoidable if the bicycle would frighten horses in the Park and cause endless runaways.

Only one private park - Woodward Gardens - granted some small concessions to the club members. Mr. Woodward rode the wheel and was a member of the club. Around the bear-pit in the garden was a circular, macadamized path. On this the wheelmen were permitted to ride at times when no others were at all likely to visit the gardens - that was early in the morning, and the wheelmen eagerly clutched at that small privilege. The bears did not molest them, being scared by the rapidly revolving wheels. The wheelmen persisted in their efforts to obtain some concessions from the Park Commissioners and sent their emissaries from time to time in order to convince those dignitaries that Golden Gate Park was not the sole and exclusive property of the wealthy.

During all that time the wheelmen stole rides in the Park during the early morning hours or late at night. They had their wheels carted out on express wagons, dump them over the fences, inside the inclosure, walk into the Park, pick up their wheels and steal a spin on the least-frequented driveway.

A committee composed of Governor Perkins, Columbus Waterhouse, Colonel de Clairmont and George Hobe waited on the Park Commissioners, once again to urge for some slight concession. The Commissioners held a meeting in the President's office of the Bank of California. Chairman Eldridge, then Chairman of the Commission, leaned back in bis chair, looking at the petitioners, most of them old men, and in tones of amazement he asked:

"Do you boys mean to tell me that you are going to ride a bicycle?"

The idea seemed almost too ridiculous to be true. Some concession was obtained, however, and members of the club - none other - were permitted to ride their wheels in the Park, but only before 7 a. m., and they were restricted to one entrance, from Stanyan street. They had to pack the machines two or three miles over a dusty road to reach that goal. The panhandle was to them forbidden ground. On entering, and as often as required by the Park police, they were obliged to exhibit a little pasteboard, issued by the club - a sort of ticket of admission - proving their identity, else they were excluded from the Park. To enjoy a spin in the Park it was necessary to rise early. To reach the place, have a ride and be gone before 7 a. m. made early-risers of the wheelmen. They kept early hours, and acquired the virtue of retiring early. In time the limit was extended one and later two hours.

The members of the club were held responsible for any violation of the Park rules and each constituted himself a detective in order to exclude intruders, whose acts might possibly injure legitimate riders.

Frank Pixley extended the privileges of the Park to bicyclists and told the club members that he had no objection to competent wheelmen riding in the Park, but cursed those who did not know how to ride and scared horses. He predicted that the bicycle had come to stay, and that its use would grow. He even consented to have a cyclery built in the Park, for the accommodation of the club, which at that time had become quite numerous and numbered among its members some of the best-known men in the community. The plan for the proposed cyclery was drawn, but its erection was never accomplished.

General McDowell was a member of the Park Commission and exhibited a spirit of liberality toward wheelmen. He was prevailed upon to grant the club similar concessions over the Presidio roads. Adjutant Kelton issued the order, couched in regulation military terms, and copies of the ordinance were posted all over the reservation. The document read like an order issued to the military on a campaign. It recited with great flourish that the members of the San Francisco Bicycle Club had been granted permission to ride on their wheels, on certain days, hours, roads, designating distances with exact limits and limiting the rate of speed, with exact precision.

Every machine in use had its pedigree, just as much as a blooded horse, and every rider knew every other rider's machine. Wheelmen recognized each other at a distance by their wheels just as a marine reporter can tell a ship by her build or rigging.

Of the original riders many still spin on their wheels, like Colonel de Clairmont, now about seventy years old, George Hobe, who is past seventy, Senator Perkins, Herman Eggers, Morris Feintuch, George Strong, Henry Loudon.

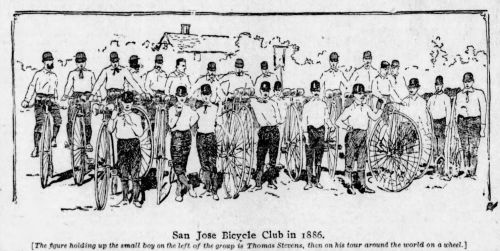

[The figure holding up the small boy on the left of the group is Thomas Stevens, then on his tour around the world on a wheel.]

The drawing abiove is quite obviously from this photograph, from the William Letts Oliver collection. More info here. - MF