TOUR ON THE WHEEL. - Pleasurable and Tiresome Experiences Wading Through Sand and Tide. - Graphic Narrative of a Cycling Trip to Southern California. - San Francisco Chronicle, 08 Sep 1894

TOUR ON THE WHEEL

Pleasurable and Tiresome Experiences.

Wading Through Sand and Tide.

Graphic Narrative of a Cycling Trip to Southern California.

This year Southern California has been the Mecca of touring wheelmen. Swain of the Acmes was the first to make the trip; then followed Osen's celebrated record performance and the almost equally famous trip of Professor Wilson and party. So graphically were the delightful seaside resorts, beautiful orange groves and healthful climate described and extolled by these parties that a general general desire was awakened to inspect the southern portion of the State in person, and among the others I succumbed to the fever which was becoming so prevalent.

I immediately began planning the trip and soon induced Dr. Lovegrove, Will Haley, Frank Fuller, Frank Hunter, George Pollard and Jack and Howard Alexander to join the party. What a time we anticipated; a regular club run, but Haley, Fuller and Frank Hunter found it impossible to go, and as the San Jose boys started some days before Dr. Lovegrove and myself could leave, we found it imperative to abandon the original intention of riding all the way through, and instead to take the steamer to Santa Barbara and join forces there.

The trip down on the steamer was uneventful, and we found ourselves in Santa Barbara on the night of July 16th. Inquiry elicited the information that the San Jose delegation had not yet arrived, and as a consequence we bad some time at our disposal to inspect the town.

At 3 o'clock, the boys not having arrived, we decided to take advantage of the low tide and proceed to Ventura along the beach, a distance of thirty miles. Some three miles out of Santa Barbara the doctor got a puncture which we could not locate and which necessitated a walk of about a mile to the next house where we could obtain a bucket of water. From there we went on to Carpenteria. [sic] over excellent roads, principally down grade. Shortly after leaving Carpenteria we struck the beach. It was now after 4 o'clock and a dense fog was rolling in, making it impossible to look ahead more than 100 yards or so. Meeting a team here the driver informed us that we could make it, although we might get a little wet. The first fifteen miles were excellent, the wet sand making making a good hard surface, but after this the cliffs became more precipitous, rising right from the water's edge and making it necessary to watch for an opportunity to run around as the waves receded. After this had been repeated several times, each passage being more difficult than the last, and knowing retreat to be impossible, with an impenetrable fog enveloping enveloping us and with no means of ascertaining when the cliffs came to an end, we began to think our chances excellent for camping on some ledge of rock.

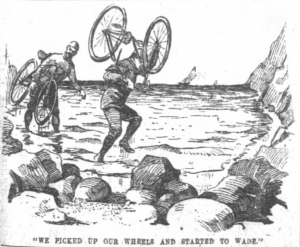

Riding as we had never done before we finally reached a point projecting out a considerable distance into the sea. There was no help for it, and without waiting to take off shoes and stockings we picked up our wheels and started to wade around in water now up to our ankles, now at our knees. Availing ourselves of the rocks where they would afford foothold we finally managed to get out of the water on the other side of the cliff, and were rejoiced to see that we had passed the worst of it. But the tide was too high to admit riding on the beach, and after a weary tramp of two miles through loose sand we arrived at Ventura, hungry and sleepy.

Leaving there next morning at 6 o'clock we proceeded, confident that our tribulations were at an end. A fairly good road extends almost to New Jerusalem, where it runs right through a river some hundred feet in width and over which there is not even a suspicion of a bridge, and consequently no alternative but to wade. Two miles beyond here the road runs through the bed of a creek for three miles and the sand is so deep that it is impossible to ride a foot of it.

We were now rapidly leaving the coast and the heat was becoming intense. The road here became sandy again, making progress very slow. We were told that what was called the long grade was about a mile ahead, so we pushed forward, reaching the top after a hard climb. The road on the descent was so steep and sandy that riding was impossible. We trundled our machines some distance before before we could remount. A mile beyond this the road forked, and taking the one to the left we followed it until it disappeared in the middle of a field. We concluded we would cut across the country rather than retrace our steps. It was two hours before we again struck the right road, and another hour before we saw a house, which we hailed with delight, as it was now 3 o'clock and we had not tasted food since leaving Ventura at 6 o'clock. But this house was deserted, as was also the next. The heat was now more intense than at noonday, and seeking the shelter of the barn we waited until the sun went down before proceeding. Fifteen miles further on we reached Calabassas, [sic] a road house and Postoffice thirty miles from Los Angeles, where after procuring something to eat, for we were faint with hunger, we remained for the night. Next morning we arose early and arrived at Los Angeles three hours after, rejoiced to be again amid civilization.

The Alexanders and Pollard arrived the next day, and we greatly enjoyed exchanging stories and comparing notes. Jack Alexander gave the following account of his trip, to which we listened with an interest born of sympathy.

"I left San Jose Thursday, July 12th, at 11 A. M. The first day's ride took me to Hollister. This is some eight or ten miles off the road, but as I had four days in which to make 200 miles, I wished to take in as much of the country as possible. Early next morning I climbed the San Juan mountains, which looked bad enough that early in the trip, but which were a Paradise compared to those encountered later. At the foot of the grade I again wandered from the straight and narrow path by taking the road through Salinas.

"From here to Kings City, a straightaway stretch of fifty miles, over hard adobe roads, the winds blow a regular hurricane at your back. Sandclouds laden with pebbles and weeds envelop vou with sudden fierceness, and large bowlders by the wayside seem anxiously waiting for a larger gust, so that they, too can join in the procession.

"Borrowing a few sticks from a neighboring fence, I fixed my coat so that it would spread out like a sail. In this way I floated along mile after mile, scarcely pedaling ten miles out of the entire fifty.

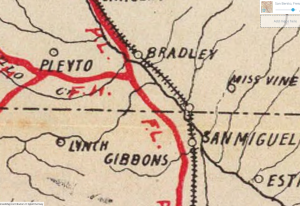

Pleyto to San Miguel, from "The Cyclers' Guide and Road Book of California", published two years later in 1896

Pleyto to San Miguel, from "The Cyclers' Guide and Road Book of California", published two years later in 1896"From Pleyto to San Miguel, twenty miles distant the road loses what good reputation it may have gained in its former course. For the first five miles the scenery is lost in the toil up and down the mountain side, and mostly up at that. At Kings City I had been instructed regarding the route. After crossing a bridge and passing two houses you were to turn to the left and from there make no turns at all but were to keep the right-hand road, there only being one other fork and that about half a mile further on. From here on to San Luis Obispo the trip was monotonous and wearisome except the coast down the Cuesta grade. Luckily I had rubber strips on my tires so that I could use my foot as a brake. Without this protection my light racing tires would hardly have reached Mexico.

from a 1919 Mead catalog, page 25

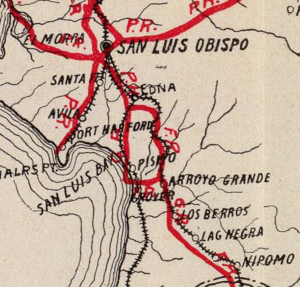

from a 1919 Mead catalog, page 25"At San Luis I met my brother, Howard Alexander and George Pollard, who had arrived safely the evening before. One of the best arrangements we had made for the trip was in having a trunk of necessary articles sent on from town to town ahead of us. So in the evening, after we had disappeared in our rooms for a short time, you would never have thought we had been traveling all day over hot, dusty roads. It was late in the morning when we left San Luis Obispo. We took a longer, and as they told us, a better route to Arroyo Grande. But If the other is worse I pity the poor wheelman who is ever luckless enough to go that way.

San Luis Obispo to Arroyo Grande from "The Cyclers' Guide and Road Book of California", 1896

San Luis Obispo to Arroyo Grande from "The Cyclers' Guide and Road Book of California", 1896"Everything went well until we came to the Santa Maria river bed, the place where the water must have turned into sand, and before the conversion there surely was plenty of water. They call it two, but I will wager we walked fifty miles in crossing it. At least that is how it seemed to me. First you climb a barbed-wire fence and tear your clothes trying to find it harder on the other side. Then you climb back again and settle down to steady walk, dragging your wheel after you. The fence ends, and you seem lost in a great desert. Walking in the wagon tracks you think the other bank will bring relief. You struggle up the other side only to find the sand stretching on and on in the straight and narrow way, the way you must go.

"But it must all end at last, and we were repaid at Santa Maria by one of the best meals on the trip. Perhaps we called all of them the best, for it only takes a few days on the road to change a consumptive into an athlete. In the sentiments of the great humorist, a few weeks' trip awheel would return an Egyptian mummy to its pristine vigor and give it an appetite like an alligator.

"We were escorted on our way by Gus Pene, A. E. Cox and Bert Coblentz. Leaving them some ten miles out we wended our way up the valley over a very sandy road. One thing which a cyclist would like to see spread all over the country is a set of distance posts, noting how far you are from the next town. It's a failing in this country for no one seems to know how far he is from any place excepting it may be - well, as I was saying we would inquire distances. One person would say ten miles. Inside of the next 300 yards another would answer fifteen. Rather slow traveling, and we often vented our feelings on the surrounding atmosphere.

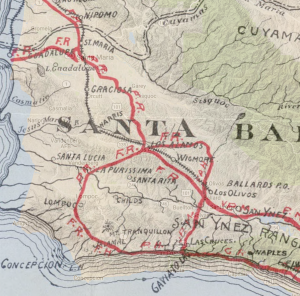

"Our route was over the steep grades of the Santa Ynez, being shorter, and if the other through Los Almas [sic] could be worse, then this is the better. So they told us, at least.

Santa Maria to Santa Ynez, from "The Cyclers' Guide and Road Book of California", 1896

Santa Maria to Santa Ynez, from "The Cyclers' Guide and Road Book of California", 1896"There are two separate inclines, both very steep from this side, but offering long, gradual coasts on the other. For three or four miles you wind slowly down the side of the mountain over hard, smooth roads.

"Here we were overtaken by darkness, but as a full moon was rising, the ride from the summit to Los Olivos, six miles away, was one not to be forgotten. After leaving Santa Ynez, five miles from Los Olivos, the road becomes most monotonous. You wind up a long, barren canyon, over rough and dusty roads filled with loose rocks and bowlders. The creek bed, where water may once have been, but which now looks as if it had forgotten what even vapor might have been, winds from side to side of the gully, leaving high abutting ledges. Up and down these we went in the most monotonous order, every new one the exact counterpart of the one just passed. As far away as you can see the same dust, rocks and sagebrush are outlined against the bleak and barren mountain-side. For the entire distance there are no houses to be seen except where the stage stops for changing horses.

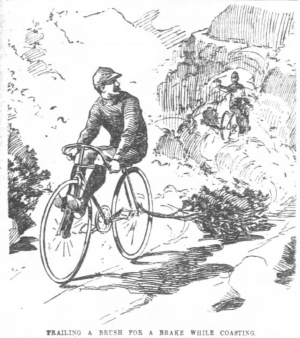

"Nothing is ever raised here except on windy days, when they raise a horrible cloud of dust. But as the wind seldom blows they make a failure of even that. About three miles from the summit the Cold springs' stopping place is reached. It is like an oasis in the midst of a desert. Here by chance are a few trees and a tiny trickling stream of water. Here we lunched, and then resumed the same course to the top. Then began our steep descent. But about two miles down the road changes and is slightly elevated for another two, when once more it plunges downward into the Santa Barbara valley. Just before reaching this slight rise I suddenly suddenly discovered that How and Polly had dismounted. I shouted, but they answered that everything was all right, so I continued onn [sic] until the road again took its downward course. From this spot I was enabled to see the place where I had left my companions. Soon I saw an immense cloud of dust, and How and Polly turned the corner dragging the famous brush pile behind them as a brake. They had struck the incline and stopped. Then they dragged it for some hundreds of yards, until they were compelled to cut it off in order to navigate. They thought to surprise me, but the joke worked the wrong way.

"Then I went on, back-pedaling most of the way down the steep and dusty road. At the bottom I waited and it was nearly an hour before the others put in an appearance. They were white with dust. At the beginning of the second grade they had tried the trick again and with great success. Only the one who rode behind was lost in such a cloud of dust that he was totally covered. Then the brush in front would smooth over the road so that the other would ride into chuck holes without seeing them. Still they said they would be willing to repeat the operation. We arrived late in the afternoon at Santa Barbara, where we expected to meet Lew Hunter and W. R. Lovegrove, but were obliged to push on to Los Angeles before seeing them."

The doctor and myself listened to this recital with interest and regretted that we had not made connections in Santa Barbara. Next day we all went out to Mount Lowe, made the ascent on the celebrated inclined railway and enjoyed a grand panoramic view of Pasadena and the San Gabriel valley. Returning to Los Angeles, we visited the athletic club, where we were most hospitably treated. Here we met Fox, Burke, McAleer, Hall and other southern stars.

On Saturday night we went to Santa Catalina, and as the little steamer approached the harbor, which is a perfect crescent, it was suddenly lighted up. Rockets shot skyward and red and green fire was burned on every hand, presenting a beautiful and fantastic appearance. Next day we rowed around the pretty little bays and inlets. Returning that night to Los Angeles, the next day we left for San Diego. There we visited the beautiful Coronado Hotel and enjoyed a swim. The temperature of the water in the open bay is over 70 degrees, and the ocean is but slightly colder.

Jack and Howard Alexander were determined to go down to Tia Juana, some fifteen miles, so that they might say they had been in Mexico. The rest of the party returned to Los Angeles, where Dr. Lovegrove wished to engage in a game of chess with Dr Lipschutz. While he was thus employed I rode out to Pasadena. The road to Pasadena is a slight incline, and the surface is sandy and almost unfit for wheeling. In fact, in no place in Southern California can the roads be said to be really good. The next day we took the train for home, completing a trip which I should advise any who may contemplate making to take early in the spring.